Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal

Canal, pump station, and Twin Peaks mined to one peak for concrete (concrete lines the CAP canal)

Currently, Tucson gets the majority of its municipal water from the Colorado River. The 300+ mile CAP canal delivers water from the Colorado River to the cities of Phoenix and Tucson and many farms ALL of which are much higher than the river. So, the water must be pumped uphill (as much as 3,000 feet) at great cost, because water is heavy, and takes a lot of energy to move uphill. Thus, the CAP canal, and all its pumps in all its pumping stations, is the single largest consumer of electricity in the state of Arizona and the single largest emitter of carbon in the state, due to the fossil fuels burned to generate the electricity. This also consumes water, since water is consumed in the generation of electricity at fossil-fuel burning and nuclear power plants; and their is some loss of water evaporating from the canal.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

The Colorado River has been designated America’s Most Endangered River due to mounting problems with radioactive, human, and toxic waste in its water, and because the river has been over-allocated to the point that so much water is pumped and diverted out of the river that its southernmost flow has ceased, crippling the Colorado River Delta’s ecosystem, economy, and cultures.

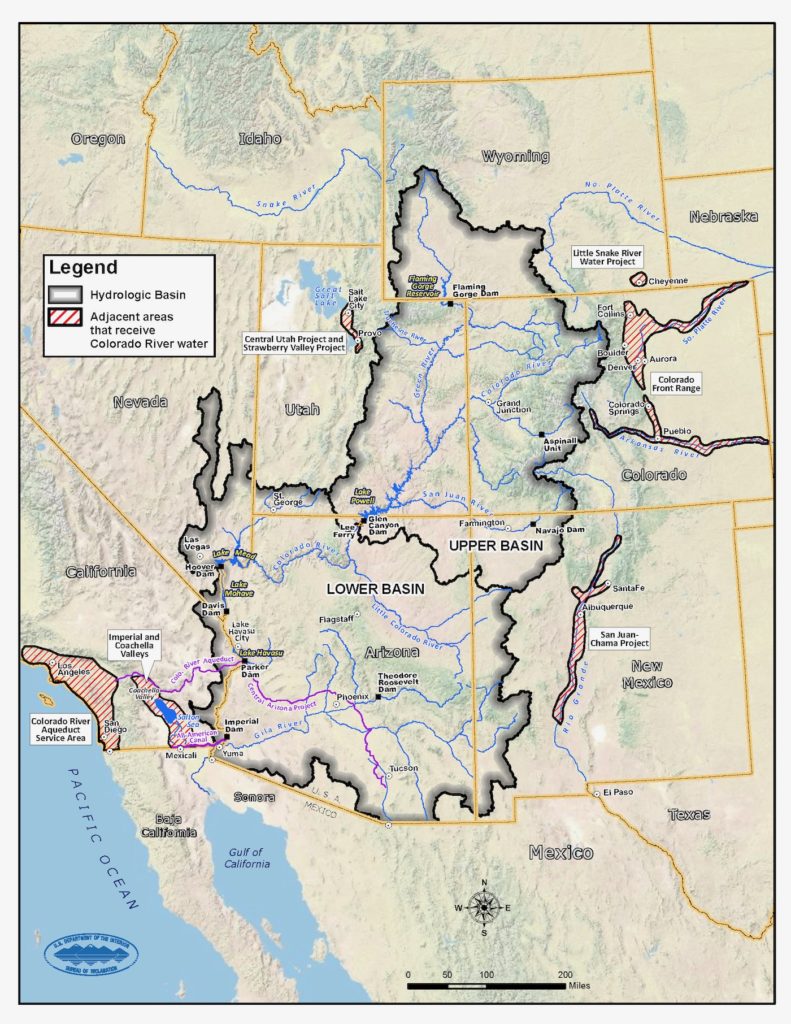

A great many communities and farms are extracting water from the Colorado River, with an ever growing number outside of the Colorado River watershed. See the map below for the Colorado River Watershed and some of the areas both within and outside of the watershed that are extracting the River’s waters…

Image reproduced with permission from the U.S. Department of Interior, Bureau of Reclamation

Due to the on-going mega-drought and the dwindling flows of the Colorado River, Tucson may soon loose 50% of its CAP water allocation.

CAP canal water was first delivered to Tucson in 1992, and CAP water has since become the primary water source for Tucson’s municipal supply.

Before CAP water, Tucson got all its water from rainfall, the Santa Cruz River, and local groundwater. The Santa Cruz River dried up from over pumping our groundwater at a rate that exceeded natural recharge from precipitation; while at the same time much of the rainwater-absorbing living sponge of dense vegetation and thriving soil life in the river’s watershed had been removed by overgrazing, tree felling, draining of wetlands, and building. That living sponge was then replaced with rainwater-draining/-evaporating pavement and compacted bare earth.

So much groundwater was, and is, pumped out of the aquifer that Tucson began to sink (and continues to in parts of the Tucson Basin), since many of the pore spaces in the soil below Tucson no longer are filled with water and they compress – this is known as “subsidence,” and leads to cracks in buildings, plumbing, and other infrastructure.

CAP water is currently used to artificially recharge Tucson‘s groundwater (see the Central Avra Valley Storage and Recovery Project [CAVSARP], another stop on this tour).

How we can do better

Tucson (and all the other communities and farms extracting water from the Colorado River) could do a much better job of helping naturally recharge its aquifer, since more rain falls on Tucson in an average year of rainfall, than all its residents consume of municipal water in a year (but we currently drain, rather than retain the majority of that rain).

That speaks to the potential of how dramatically we could enhance our free, local water resources if we were to harvest, rather than drain the rain (as we currently do). At minimum, this would indirectly help recharge groundwater and river water by reducing the amount of water we extract/pump from our aquifer, or surface water from the Colorado River. Though harvesting water as I advocate can also helps directly recharge (give back) water to the aquifer and river flows. See the latest full-color editions of Brad Lancaster’s books Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond for many easy ways of doing this.

Many of the rural areas of the Tucson Basin and Avra Valley watersheds are also rapidly draining soil and stormwater due to disturbance and resulting erosion, whereas in the past these watersheds had much more vegetative cover, which helped slow and infiltrate more of the rain and stormwater. See here for some more info on this, and efforts to rehabilitate sections of the Altar Valley watershed (a subwatershed of the larger Avra Valley watershed).

See the video below for some of the many benefits to the river, people, and sea when we allow the Colorado River to again flow all the way to the Colorado River Delta and the Sea of Cortez…

By reducing our extraction of Colorado River, and increasing natural recharge throughout its watershed we can have more of this, and more vibrant, hydrated communities throughout the Colorado river watershed.

Where:

10219-11791 W Twin Peaks Rd, Marana, AZ 85653

32.38023689507858, -111.19445913775314

Hours: The road pull off, and view from there is always open. To get to the viewpoint from the hill on east side of road, you must crawl under a barbed wire fence and enter State Land.

Cost: Free

Pets allowed

This location is included in the following tours:

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1