Avra Valley Swales

Built by Civil Conservation Corps in the 1930s, and then abandoned.

A great site to see what happens when we walk away. Where things are well-designed and built—life can flourish; but where they are not—things can unravel, and may make things worse.

These swales are somewhat famous in the permaculture world due to them being featured in the dryland episode of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s 1991 documentary the Global Gardener featuring Bill Mollison, author of Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual. See the footage in the video clip below…

Slope and water flow is from right (east) to left (west)

Screen shot from GoogleMaps (satellite view).

Australian Permaculture teacher Geoff Lawton also produced a video on the Avra Valley swales, after I took him there (as one of my teachers, Tim Murphy, originally brought Bill Mollison, and later myself, to the swales).

I’ve been visiting the swales, often guiding students there for over 20 years. It is impressive and inspiring to see the swales’ beneficial effects, and how much more life can grow when you slow and infiltrate the stormwater flow across the landscape (I’ve been on site in big rain events when sheet flow across the landscape ranges from ankle to leg-calf deep).

It is also very informative to see how things change from season to season throughout the year, year after year.

You learn to identify plants as seedlings, adults, and in both their dormant state and their vibrant growth state. Annual plants come and go. Sometimes areas are jungle-like. Sometimes they are bare.

I like to try to read water patterns when all is bone dry by looking for remanent tracks, coming back in a storm to watch the actual flow; then coming back again within a week of the storm to see how the water flow I had observed reshaped the land, sprouted new growth, and formed new tracks. These repeated observations enhance my ability to read and understand tracks, along with what causes them. I can then better design to create desired flows, and avoid the destructive ones.

Note how lush the vegetation is on the upstream side of the berm compared to elsewhere.

The trees in that lush vegetation are over 20-feet (6-meters) tall.

Blue arrow denotes water flow.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 8-24-2014

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 8-24-2014

Velvet mesquite trees are the dominant growth on the berms and at the water inlet.

The inlet is also the overflow point, as the harvested water backs up on itself once the charco fills.

Photo was taken from downstream berm looking upstream.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 8-24-2014

But there are also some bad effects,

and I think a more critical eye is essential to avoid repeating some of the project’s mistakes or oversights.

For example, if you look closely at the aerial photo, you’ll see that where swales have diverted water away from pre-existing water channels, those channels have been dehydrated downstream of the swales, and the remaining vegetation within them is a shadow of what existed before. This perhaps would not have been the case if some of the swales’ overflow had been directed to, rather than entirely away from, those natural water ways.

The green arrow points at a once well-watered and well-vegetated waterway that has been dried out and denuded due to the the upstream swale (to right of arrow), which now redirects the water flow to two new, and eroding (downcutting) waterways.

The new waterways begin at each end of the swale, where the swale has channelized (rather than spread out) the flow at these two overflow points.

Compare the vegetation density of the waterway coming into the swale, and the three waterways just downstream of the swale.

Smaller strategies spread throughout, and better integrated with the waterway and watershed could’ve enhanced more area without negatively affecting areas below.

See here for an example in a different context.

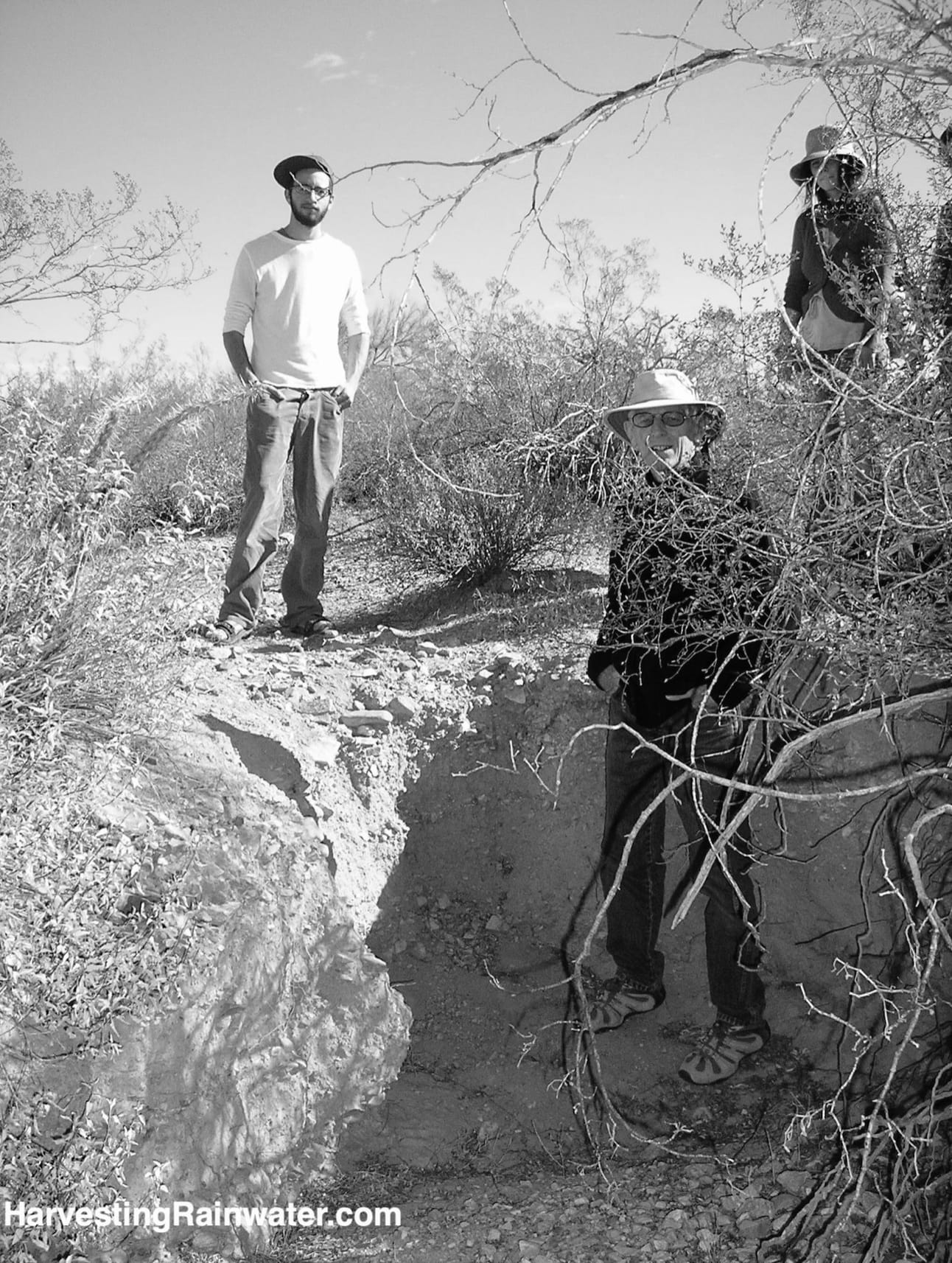

Where swales have concentrated, deepened, and channelized what had previously been spread out, shallow, sheet flow of water, head cut erosion has formed which threatens to unravel the swales (see head cut photo below).

If not checked, this headcut erosion will continue moving headward (upstream); and it will cut into, drain, and dehydrate the swale’s basin.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 5-17-2012, reproduced with permission from Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition.

Had the swales’ overflow been designed to spread out and calm its flow (and support more stabilizing vegetation), rather than channelize the flow and increase its ability to pick up and carry more sediment (and thus create more erosion), we would likely have a much better result today.

Where: Located off N Sandario Rd, almost exactly 2 miles south of the intersection of N Sandario and Mile Wide Roads. Park your car on side of road here: 32°13’09.7″N 111°13’04.8″W

Then go under barbed wire fence, enter Bureau of Reclamation land, and walk upstream, due east about a quarter mile to the most downstream spreader swale at: 32°13’09.6″N 111°12’53.7″W

You can then continue east to see more swales (see screen shot from GoogleMaps). The large, well-treed half-moon shape structure is a charco or ephemeral pond created with a half-moon-shaped berm (it is not a swale).

Hours: Pull off on side of road is always open. To get to swales you must crawl under a barbed wire fence on the east side of the road and enter Bureau of Reclamation land.

Cost: Free

For other examples of different civil conservation corps water conservation strategies see:

Historic check dams in the Catalina and Tucson Mountains

Sus picnic area and check dams

This location is included in the following tours:

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1

This is THE book to start with.

It gives you the integrated vision, concepts, and approach.

And be sure to read appendix 1: Patterns of Water and Sediment Flow with Their Potential Water-Harvesting Response.

Volume 2

This book gives you step-by-step instructions on how to create many different types of water-harvesting earthworks for different conditions and contexts, and grow well-suited vegetation that will thrive without you after establishment.

Be sure to read the book’s water-harvesting principles and the various case studies and stories of people applying those principles for different effects.

And read the principle set specific to in-channel strategies, and their examples in chapter 10.