Shifting dehydrating, degrading ephemeral water channels to better-vegetated, rehydrating, agrading channels with Bill Zeedyk-directed efforts in Altar Valley, Arizona

By Brad Lancaster

with gratitude to Bill Zeedyk for his edits, feedback, and mentoring

www.HarvestingRainwater.com

Starting January 2012, Bill Zeedyk and Steve Carson directed the largely volunteer-installed on-the-ground work in a collaborative conservation/restoration project in the Altar Valley in southern Arizona, aiming to reverse the erosive down cutting of water channels/arroyos and dirt roads at the Elkhorn/Las Delicias Watershed Restoration Demonstration Project site by using three primary strategies:

• induced meandering within the water channel with one-rock-high baffles and one-rock dams seeded with native restoration seed mixes;

• treating a 3.25-mile stretch of dirt road with 54 rolling dips that drain stormwater off the roads and passively irrigate roadside vegetation, and 14 road crossing stabilization structures stabilizing road crossings of streams;

• upland restoration with one-rock high rock media lunas and one-rock dams upstream of the main water channel

The project and its effects were and are extensively monitored.

As Bill Zeedyk says, the intent of the project was to reverse the trend by shifting from erosion of soil to deposition of soil.

It has done that.

In addition, moisture now lingers longer in the watershed, enabling more vegetation to grow, better capture sediment, and hold and build soil. All this also reducing flooding and erosion downstream.

I just attended the 10th anniversary tour of the project, and wanted to share photos and videos taken over the years at the project, plus links to data from the project’s extensive monitoring, so you can see some of the positive results.

Work within one of the main water channels/arroyos

Green arrow shows the soil level before the water channel bed erosively down cut. Part of velvet mesquite tree below the green arrow is all exposed roots.

Bill Zeedyk is 5 feet 6 inches tall, and stands beside the tree.

Bed of water channel has down cut so much that water from larger flow events can no longer reach, and spread out onto the original adjoining floodplain at the green arrow level.

Red arrow shows the location of the downstream road crossing of the water channel, where the road crossing was stabilized with a rock grade-control structure.

Blue arrows show how water flow will be induced to a more meandering path due to the one-rock high baffle (the woman below the red arrow is sitting on).

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Reproduced with permission from Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition

Bill Zeedyk points to where the soil level was before the water channel bed erosively down cut. Part of velvet mesquite tree below the green arrow is all exposed roots.

Comparing to previous photo from 2012, note how much more fine sediment is in the channel bed. Larger rock, and the rock baffle and one-rock dam can no longer be seen as they are now buried in accumulated sediment. Vegetation is now much denser on a widening floodplain within the arroyo.

Sediment accumulated on the upstream side of the rock grade-control structure (stabilizing the downstream road crossing of the waterway) has backed up to this point raising the bed of the channel by at least one foot.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Media luna structures above the water channel (scroll down for photos) are also helping heal this part of the channel. The media lunas have helped slow, spread out, and infiltrate sheet flow in upper reaches of this water channel’s watershed to re-wet and re-vegetate about 2 acres of previously bare draining and eroding land.

By reducing the volume, depth, and speed of peak flow of stormwater (by spreading out the flow) within and above the water channel, the force and ability of the flowing water to carry sediment is also reduced. So, you then see more smaller particles of sediment compared to the larger particles seen before restoration work.

As the water flow is spread out and slowed down, more water saturates the soil, and prolongs the length of the time the water flows and lingers in the landscape, enhancing the growth of more water-slowing and -spreading vegetation.

As more vegetation grows, the roots increase the permeability of the soil, which then increase the volume of water that infiltrates the soil — especially within the site’s otherwise hard, exposed subsoil. Vegetation continues to grow, and sets is roots deeper and deeper as it also grows a thicker and more absorptive sponge of organic matter above the soil’s surface; more water is slowed and infiltrated, and more vegetation grows—a beneficial feedback loop.

When assessing the Elkhorn/Las Delicias Watershed Restoration Demonstration Project site and planning potential interventions, local healthy watersheds and healthy reaches of water channels, such as this one, were sought out and studied, as a guide for what used to be pre-erosion, and what to aim for with restoration.

Note here how wide the channel is, and how the adjoining vegetated floodplain is still within easy access for large flow events to spread out onto and hydrate more of the larger watershed. A lot of the water flow is probably subsurface, within the pore spaces of the sediment and soil, especially after surface flow subsides.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

This rock structure on the downstream side of the dirt road crossing the channel has raised the bed of the channel on its upstream side.

Footer rocks at the base of the downstream side of structure reduce erosive scour caused by water flowing over and off the structure.

Structure built by Steve Carson of Rangeland Hands, Inc.

Downstream of the rock structure stabilizing the road crossing, is a one-rock dam (ORD). The ORD raises the brim of the scour pool that will form at the base of the road-stabilizing rock structure as the water falls off the steep downstream side of the structure. After raising the brim of scour pool, the ORD will also keep the elevation of the surface of the pool constant, reducing scour (the pooled water will diffuse the force of the water falling into it), while also enabling the pooled water to linger longer post-rain (benefiting wildlife and livestock).

Photo: Brad Lancaster

This rock structure on the downstream side of the dirt road crossing the channel has stopped the erosion of the road and channel bed, and enabled significant vegetation establishment, especially on its upstream side where the channel and water flow is now much wider, and slower, enabling more moisture to infiltrate the accumulating sediment.

There is some erosive side cutting from water flow cutting around the sides of the structure, but this can be easily fixed by adding more rock on the sides, and raising the elevation of that rock, so more of the flow is focused to the lower, middle section of the structure.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

White rock structures can be easily seen from the air. Largest structures stabilize the dirt road crossings of the water channels. Upstream (left) of dirt road, you can see both in-channel structures such as one-rock dams and rock baffles, and upstream of the water channels you can see media luna sheet flow spreaders and sheet flow collectors.

Photo: U.S. Border Control, courtesy of Altar Valley Conservation Alliance

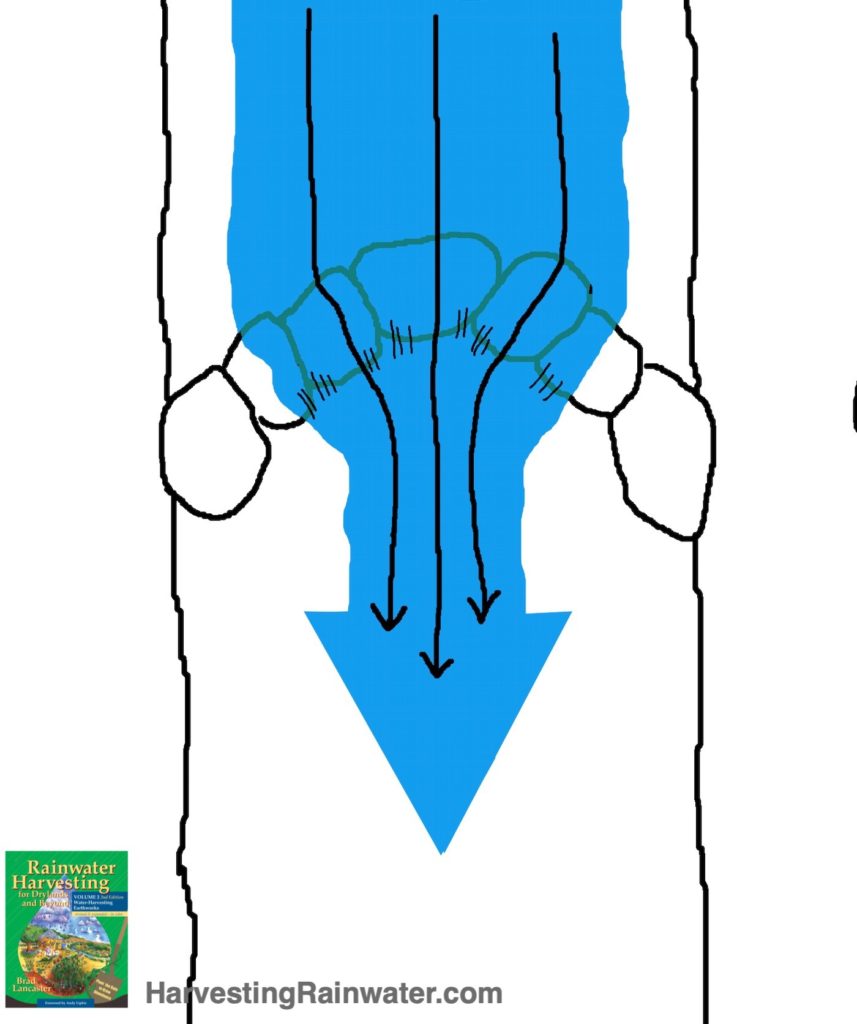

Blue arrows denote how one-rock-high baffles will induce a more meandering water flow. A rock baffle nudges more of the flow and its force into the opposing bank to erode it, widen the channel, and reduce the steepness of the channel. Sediment from the eroding bank will then be caught in the next downstream baffle and the point bar of accumulating sediment and vegetation it will help grow. Compare to next image taken four years later.

Photo: Altar Valley Conservation Alliance

Flow arrows added by Brad Lancaster

Compare to the previous image.

Trees lack leaves and grass is yellow because photo was taken in winter when vegetation is seasonally dormant.

Note how much smaller the particle size of sediment within the water channel now is compared to pre-restoration work conditions. You can no longer see the larger rock and cobble. Instead, you see fine gravel and sediment.

The rock structures are covered in accumulated sediment.

They did not wash away.

We have a whole lot more vegetation.

All this tells us water is flowing slower and longer.

Much of this is also due to the effect of media lunas in the upper part of the water channel’s watershed, which lower the peak of the flood flow and lengthen the flow’s duration.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Blue arrows denote how a one-rock-high baffle will induce a more meandering water flow. A baffle nudges more of the flow and its force into the opposing bank to erode it, widen the channel, and reduce the steepness of the channel. Sediment from the eroding bank will then be caught in the next downstream one-rock dam, the next downstream baffle, and the point bar of accumulating sediment and vegetation the baffle will help grow.

Sediment originating from upstream will be deposited on the point bar that this baffle (seen in this photo) will help grow.

Compare to next image taken 10 years later.

Photo: Altar Valley Conservation Alliance

Compare to the previous image. Note the large, well-vegetated point bar on the left that has formed on the downstream side of the rock baffle. This point bar acts as a floodplain onto which larger water flows will spread and infiltrate.

Compare to previous image taken 10 years earlier.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Compare to next image taken 10 years later.

Photo: Altar Valley Conservation Alliance

Compare to the previous image taken 10 years earlier. The rock baffle is now half buried due to agrading sediment.

This is the first and only place where we have a well vegetated floodplain on BOTH sides of the channel. The channel is recreating an active floodplain. It is minor as far as the length of the channel is concerned, but it is an indicator of the recovery process underway.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Compare to next image taken 10 years later.

Photo: Altar Valley Conservation Alliance

Compare to the previous image. Note how much of the bank opposite the baffle has eroded away, and how much more meandering, flatter (less steep), wider, and shallower the channel now is.

The steep V-shape of the banks will be further eroded down, and further widen the channel. The active flow channel is less than the nicely evolving flood plain, it’s just not apparent in this photo.

Another key thing that happened here, was there was a confluence of another channel (where large section of right bank has disappeared—compare to 2012 view), which will also be further flattened, and the floodplain will further widen and get better vegetated.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Sometimes Bill Zeedyk likes to create or enhance ephemeral pools of water with a cross-vane structure that concentrates flow to the center of the channel where there is more drop due to existing conditions (such as the large boulder around which the structure was built), and force from the falling water to scour a pool within the channel.

A one-rock dam on the downstream side helps catch sediment scoured from the pool, while also deepening the pool, and controlling the grade/elevation of the channel bed so the falling water does not undercut the cross-vane structure.

These structures must be maintained over time. Here, some of the anchoring rocks on the downstream side of the one-rock dam have flowed away. I replaced the missing rock with larger rock after this photo was taken.

Note that maintenance is not always necessary if large enough rock (which will not move) is used, the rock is of good composition, and the quality of the work is good and robust.

Compare to next photo of a different cross vane installation photographed in rainy season.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Rock work moving up the banks, and curved downstream, lessens depth of water along banks, reducing the water flow’s erosive force, which might otherwise erode around the structure.

Water spilling over ends of the structure (in big flow events), along the creek banks, is directed into the pool below the structure. The pooled water diffuses the force of the incoming water, while enhancing water availability for wildlife and livestock.

Designed by Bill Zeedyk. Hand-built by Pima County road crew in 2007. Altar Valley, Arizona.

Reproduced with permission from “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition.”

Thus, this shape (used in a cross-vane) helps direct water to the center of the channel.

Reproduced with permission from Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, 2nd Edition

Rolling dip drains should be placed where the landform will maximize the slowing and spreading of the stormwater over a wider area to generate a living sponge of vegetation.

This is largely working as intended, but see next photo for something that must be addressed.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, taken 10-24-2016.

Rolling dip installation had occurred 1-14-2012.

The water flow needs to be directed away from this steeper slope or the headcut erosion must be stabilized perhaps with a rock-mulch rundown. Photo: Brad Lancaster, taken 10-24-2016

More on harvesting water from dirt roads with rolling dips

See here for images and more

Work upstream of the main channels

The rock is laid only one rock high, but at least 5 rocks wide on contour of the existing landform. Native restoration seed mix is laid on ground before rocks are placed (to jumpstart the vegetative response). Note that this rock is much larger than necessary for this structure as it is dealing with calmer, shallower, sheet flow. Grapefruit-sized rock would’ve been sufficient. Ideally largest rock is placed on the most downstream row.

Compare to next photo.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

This area of the project has very eroded soil that was crippled in its water-holding capacity as can be seen in the foreground on the downstream side of the structure. But within and upstream of the structure soil, organic matter, seed, and water collects and lingers, thereby building a living sponge that further slows, collects, and grows top soil, organic matter, seed, and longer-lingering water.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Sheet flow collector media lunas damaged from the last flood must be repaired or will will loose them. They need a better splash pad on the “hounds teeth” where the structures cross emerging erosive rills. The issue is these structures were built by machine and the rock was dumped in place, rather than carefully laid by hand. The largest rock should’ve been laid in the middle of the structure where it crosses the rill erosion.

Also, some water is flowing around the edges of some of the media luna structures. This can be fixed by adding rock to their ends, ensuring the ends are higher in the landscape than the middle of the structure, so water flows over and through the structure—not around it.

Note how largest rock used in structure is in the most downstream row. Most downstream row has just been laid here, within an anchoring trench. The rest of the rock will be laid on existing grade upstream of the anchored row of rock.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Native grass seed laid down before rock in structure has germinated, and grows a living seed bank that can help regenerate soils further and wider afield.

Livestock and four-legged wildlife does not like to walk on the rock, further encouraging new growth.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

The topography, in the four photos immediately above, is typical of what the valley floor looked like before headcut erosion and resulting gullies arrived and drained the valley.

The erosion was due to severe overgrazing, which removed much of the vegetative cover of the land, which then sped up the flow, depth, and force of the water draining off the land. Other practices that similarly drained and dehydrated the land were irrigation diversions and railroad embankments that channelized sheet flow; dirt roads that diverted, captured, and channelized sheet flow; and fire suppression.

The main channel of the Altar Valley Wash (downstream from these photos) then erosively down cut, and all tributaries draining into the down cut Altar Valley Wash then also down cut—starting at headcuts formed where water flow from the tributaries dropped over a newly steepened drop into the recently down-cut Altar Wash. The whole Altar Wash and its tributaries throughout the Altar Wash watershed down cut and head cut up valley.

So, the four photos above, show a relic of what the landscape would’ve looked like without gullies. Though it would’ve been better vegetated.

Erosion caused by wagon roads is what really caused the whole system to originally degrade, plus there was an irrigation dam upstream in the Altar Wash that blew out in the early 1900s. When it blew out, flows got caught in the wagon wheel ruts that were paralleling the water channel. Ruts were straighter than the meandering channel so the paths of the ruts were steeper, water flowed faster within them, and easily carried away the fine clay soils. This started the whole unravelling.

It was made worse by the irrigated pastures on the ranch that is now the Buenos Aires Wildlife Refuge.

Due to erosion from road and irrigation ditches, head cutting and down cutting started (due to main channel being incised) and this head cutting and down cutting continues to this day.

It is hard to prioritize where to do grade control work in the watershed, since there is such a large need throughout.

So, at least encourage restoration work wherever it is welcomed by the land owner, manager, volunteers, etc. Such work could be on the refuge or any of the ranches where channel incision is still occurring.

For as Bill says, “You can lead people, but you can’t push a rope.”

Videos of the project

See here for part one video

See here for part two video

For more information

• See the Altar Valley Conservation Alliance website at:

https://altarvalleyconservation.org/

For more info specific to their Elkhorn/Las Delicias project see:

https://altarvalleyconservation.org/our-work/conservation/projects/elkhorn-las-delicias-watershed-restoration-demonstration-project/

GIS analyses for 10-year evaluation

Altar Valley Conservation Alliance & ranch-based water harvesting

• See Bill Zeedyk’s books:

Let the Water Do the Work: Induced Meandering, and Evolving Method for Restoring Incised Channels

A Good Road Lies Easy on the Land: Water Harvesting from Low Standard Rural Roads

Note that Bill Zeedyk and Steve Carson use the book in workshops for County dirt road crews. Such workshops should be ongoing.

• Want to meet, work with, learn from Bill Zeedyk?

Stay current with the Altar Valley Conservation Alliance events

and

the Albuquerque Wildlife Federation—especially its events/restoration projects at Fort Union Ranch in northern New Mexico—Bill will be there!

• Harvesting Rainwater for Hikers, Wildlife, Livestock, Oases, and More

- and read…

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1

Especially…

appendix 1: Patterns of Water and Sediment Flow with Their Potential Water-Harvesting Response

Bill Zeedyk helped me develop this section of the book.

Volume 2

Especially…

chapter 7 for rolling dips used to harvest water off dirt roads in Altar Valley and elsewhere.

chapter 10 for numerous in-channel strategies including one-rock dams, sheet flow collectors, sheet flow spreaders, rock-mulch rundowns, and induced meandering.

Bill Zeedyk shared extensive information and editing for these chapters.