Growing the Soil-Carbon Sponge by Tweaking Trails, Irrigation Line Protection, & Erosion-Control to Harvest Rainwater, Soil, & Seed

By Brad Lancaster

www.HarvestingRainwater.com

In 2018 and 2019 I had the pleasure to work with Rob Kater and crew of Native Resource International to incorporate stealth water- and soil-harvesting strategies into an expansion of the Boyce Thompson Arboretum with the Wallace Desert Garden collection that was being transplanted from Scottsdale, Arizona to the Arboretum in Superior, Arizona where average annual rainfall is 18 inches per year.

It was a massive project with hundreds of full-size specimens of trees, shrubs, and cacti being planted—many on steep slopes. The resulting disturbance from the large equipment used to dig the planting holes and transplant the new specimens on the slopes was significant. More disturbance came with the creation and expansion of trail systems and irrigation lines throughout the collection.

Rob brought me in to integrate passive water harvesting and more. On-site rock was abundant. So, I worked with Rob’s crews to create Bill Zeedyk-inspired sheet flow spreaders, one-rock dams, rolling dips, rock-mulch rundowns, and hybrids of all of the above that would spread out and infiltrate runoff flows that otherwise would’ve focused into erosive rills and gullies. Though to be clear, while I guided that work, it was the Native Resources International crews that did the work. They were incredible! Extremely hard working and hungry to learn new strategies and practices. I only came to the site a number of days to mark out and instruct on strategy locations, construction and seeding techniques; and give feedback on work done. The crews worked for weeks.

It was a great opportunity to get these practices into a public site with an educational mission, and to work with a company that could incorporate this water- and soil-harvesting approach into many other projects and contexts.

Sheet flow spreaders

Half-moon-shaped media lunas or sheet flow-spreaders were used on contour to slow, spread, and infiltrate runoff flows across the landscape, and stabilize new plantings and downstream trail borders. Often, we were able to increase their function by also placing them on contour over sections of irrigation lines running to the transplanted collection specimens. This way the irrigation lines were also well protected and would not be washed out and exposed by runoff (in some locations there was no soil beneath the irrigation lines, just bedrock).

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Though invasive red broom grass [Bromus rubens] (right side of photo) germinated along with the native grass (left side of photo). This red broom is growing throughout the site, including well above the water harvesting installations, so its seed was clearly abundant before our work.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Native grass seed was sown within these and all other structures in order to jump start the vegetative living component of structures. The vegetation stabilizes the structure with its network of roots, increases water-holding and runoff-slowing capacity, builds soil, sequesters carbon, and creates more wildlife habitat. Thus, we grow the soil-carbon sponge.

Diversion swale/rolling dip hybrids

Diversion swale/rolling dip hybrids were also used to divert runoff flows off trails, to sheet flow spreaders that then calmly and productively distribute the diverted runoff to more downslope vegetation. The challenge of any trail, road, or driveway across a slope is that the trail can very easily intercept relatively calm, shallow, spread out sheet flow runoff coming from the slope above, then speed up, deepen, and channelize the flow—resulting in the trail becoming an eroding water channel, while dehydrating the slope below that no longer receives the runoff it did pre-trail. Our strategies aimed to keep pre-disturbance sheet flows intact, and enhance those flows by slowing them down and infiltrating a larger volume into the soil throughout the watershed.

While it is common to see diversion structures across hiking trails that drain water off the trail, what is typically lacking is consciously locating the diversion/drain where it will perform the maximum benefits for the landscape it waters. Don’t just drain the trail, but do so in a way that maximizes the good it does to the landscape it drains to by maximizing the slowing, spreading, and infiltrating of the drained water into soil and vegetative life. We spread out the drained water, rather than concentrating it (which would increase its erosive potential). With the work at the Arboretum, our goal was to always follow the principles laid out by Bill Zeedyk in his book Water Harvesting from Low Standard Rural Roads, but in this case in the context of dirt hiking trails, rather than dirt roads. We especially focused on the principle to always look for the location with the best chance to drain a road or trail. The chance providing maximum good.

Sheet flow spreader/rock-mulch rundown hybrids

Sheet flow spreader/sheet flow collector/rock-mulch rundown hybrids were used on the downslope edges of trails and transplants to stabilize both. Trails were regularly dipped to drain water off the path and over the structures. Tops of structures were kept lower than the edge of path so they would allow runoff to spill off the path and over the structure, as opposed to the structures keeping water on the trail.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

One-rock dams

Many one-rock dams were used across drainages with a wonderful vegetative response. They were also used to cover and protect irrigation lines running across drainages.

Rerouting paths for people to enhance the health of paths for water

Since foot traffic impedes stabilizing, vegetative growth; sections of trails were rerouted out of water drainages so the drainages could readily revegetate. The trail crossings of the drainages were then stabilized on the downstream side with one-rock dams.

Go and check out the work

The work was done along the African Deserts Loop and Sonoran Desert Loop trails. And far more work was done than is represented in the few photos I’ve shared here. But as I mentioned at the beginning, the strategies are stealth. They were meant to disappear into the landscape as they were built to look natural. Their forms and placement were all inspired by observation of the natural flow of water and sediment. Besides, the structures themselves are not that important. What is important is what is the effect of the structures and the overall work. We can keep learning by observing the changing effects over time, fix/maintain if and where needed, and evolve our practices in future projects so they will help regenerate more life in a way that gives back more than it takes.

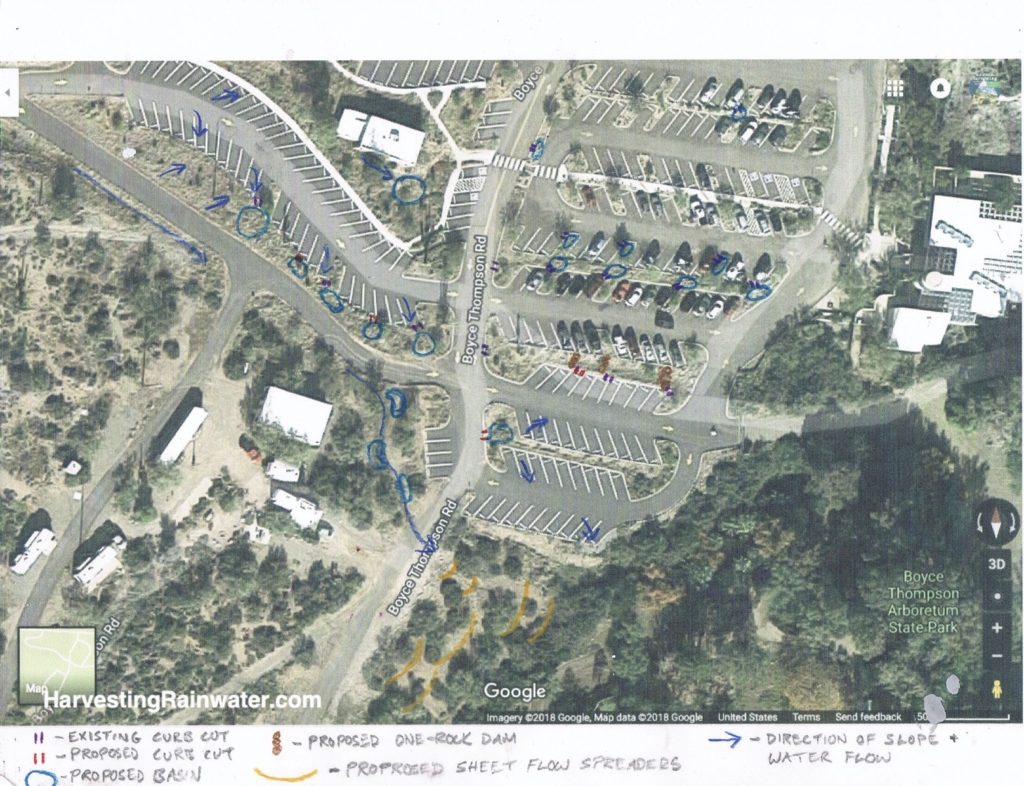

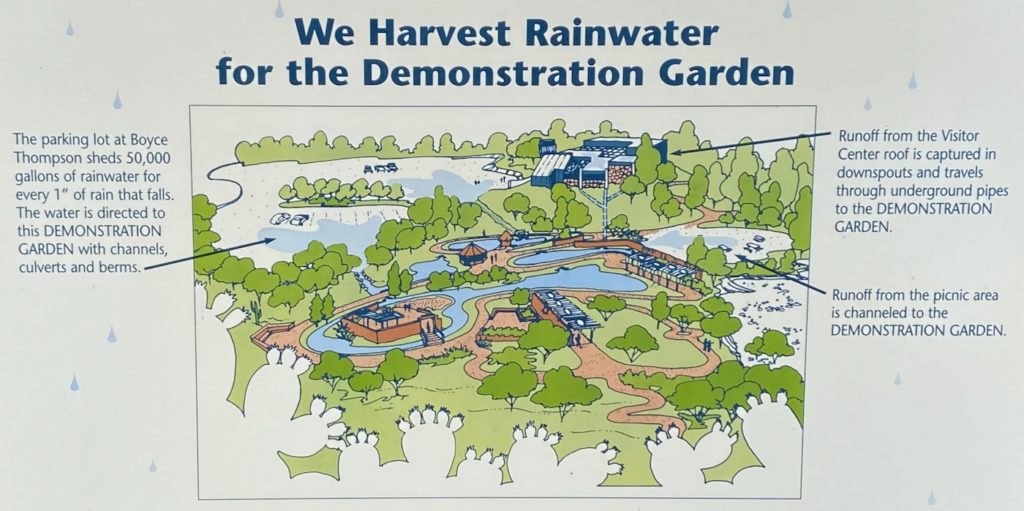

Parking lot runoff harvest potential

As a post script, early in the project Rob asked me to draw up a quick plan for how the landscape within and around the Arboretum’s parking lot could be retrofitted to harvest more rainfall and runoff from parking lot, roads, and buildings (you can see the plan below).

The parking lot currently sheds 50,000 gallons of rainwater for every 1-inch of rain that falls on it. All that flow currently flows through some of the Arboretum’s gardens before overflowing into Queen Creek. It is great that some of that water is harvested within the gardens, but far more could be harvested than is currently occurring; which would help recharge the Arboretum’s aquifer—essential to ensure that groundwater extraction does not exceed replenishment.

Should the resources and will arise at the Arboretum, perhaps some or all of the water harvesting retrofit could be implemented. Though, it is always less expensive and easiest to do so at the time of the initial design and construction, rather than a retrofit.

For more info on how to design and build the strategies discussed here and plenty of others:

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1