Harvesting Rock Water and More in Kenya

by Brad Lancaster © 2016

www.HarvestingRainwater.com

Earlier this year, while visiting the Laikipia Plateau, Kenya, I saw some of the worst erosion I’ve yet witnessed, while also experiencing a variety of growing oases. The three oases I’ll describe here are:

1. The capture of rock water (runoff from a large bedrock outcropping) into a cistern and plantings below

2. Twala Cultural Manyatta—a Maasai women-led culture and ecology program

3. Managed livestock grazing in wildlife preserves

1. The capture of rock water

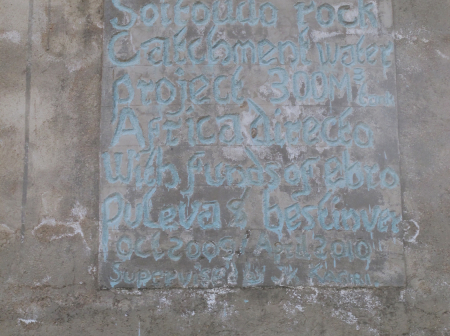

The rock-runoff cistern has a capacity of 79,000 gallons (300 m3) and was built in 2009, thanks to Catholic Sister Katia’s fundraising and organizing work with the Naatum Women’s Group in the Soit Oudo region of Lapikia District, Kenya (figs. 1-4).

Before the tank was built, area women would walk 20 km to get to water that they would dig out of the sand in natural drainages before carrying it back home. The more the watersheds of those drainages were degraded, the less water the water flowed in the creeks, and the farther the women had to walk.

Animals are not allowed in the cistern’s catchment to reduce the chance of animal droppings contaminating the water. And sediment traps precede the inlet to the tank (figs. 1 and 5).

Joseph Lentunyoi of Laikipia Permaculture Centre has since worked with the Naatum Women’s Group to enhance the potential of the system. He secured funding from LUSH Cosmetics to help repair the cistern’s plumbing, repair the land below the cistern by fencing out livestock, and plant rain and runoff via water-harvesting earthworks (fig. 6) to support native aloe secundiflora and other plantings (fig. 7). The aloe is used by the women to make soap and other products, and it is sustainably harvested and sold to LUSH for some of their products. The leaves can also be fed to chickens and used to treat malaria. Production is enhanced with beekeeping (fig. 8) and the capture and reuse of on-site nutrients such as those harvested from a newly-built compost toilet (fig. 9).

The women of Naatum (fig. 10) manage the cistern, its water catchment, and the fields below. While we were there they were in the process of building a traditional home (figs. 11 and 12).

Enough water is currently captured within the cistern to provide 80 liters of water per family per day. Water is free for the women of Naatum, while non-members must pay 50 shillings per month for access to cistern water. Another, upper cistern is desired on a different part of the rock catchment so it can be used for domestic purposes, while the lower cistern can be used for the growing farm.

You can help by attending a workshop with the women of Naatum and the Laikipia Permaculture Centre, and/or making a donation. Information on both can be found here.

2. Twala Cultural Manyatta

I was extremely impressed with our guides, Rosemary Putinoi and Priscillah Sente, and all the other women of Twala Cultural Manyatta. They convinced the men in the area to give the women land that the women would control in order to improve the lives of all. This was a coup in this male-dominated society, and very effective.

The women have greatly enhanced the livelihoods of all families in their community by growing native aloe secundiflora and other crops for their own use and sale, making and selling—direct to the customer—traditional Maasai jewelry, leading eco and cultural tours, producing fruit syrup from invasive prickly pear cactus, and much more.

All is done in a way that builds upon and strengthens many of the Maasai traditions, while also consciously evolving in a changing world.

For example, you can join Rosemary as she walks with the baboons.

In the past there was more conflict between area humans and baboons as a result of the baboons’ stealing water and food. This increased as erosion and deforestation of common/wild pasture land increased, due in part to growing numbers of grazing livestock and less-active management of that livestock since kids who used to shepherd the animals now went to school. Then non-native prickly pear cactus (Opuntia sp.) started to fill the voids and take over where native vegetation was disappearing.

The thorns in the prickly pear fruit cause problems for the livestock that eat it, but elephants and baboons love it. Baboons have learned to rub the thorns off the fruit before eating it, and they also eat the prickly pear seed picked out of elephant dung. Thanks to the abundance of this juicy fruit the baboons now rarely steal water and food from people. And the baboons’ health is improving.

Mother baboons now seem to be producing more children with the presence of Opuntia. Prior to the prickly pear, baboons would live 30 years. Now it seems they live 50 years. And the hyraxes that live with baboons among the rock outcroppings have more food as they eat the seed from the baboon droppings.

Maasai did not traditionally walk with baboons; instead they’d kill them if a young goat was killed by a baboon. But now people value the baboons as the guided baboon walks bring in money, which is fairly distributed throughout the community.

Rosemary trained every day with the wild baboons and the Uaso Ngiro Baboon Project for 7 months to build trust and to learn all that she now teaches and continues to learn, as on every walk the baboons’ behavior is observed and recorded. Rosemary is now seeking to train younger generations to succeed her.

I had meant to share far more about Twala with you all, but I lost my notes and photos from that part of my journey, though you can watch this video, and perhaps even go visit. My stay with all of them was a highlight of my trip.

3. Managed livestock grazing in wildlife preserves

This next bit will just be a lure for you to think about and pursue further.

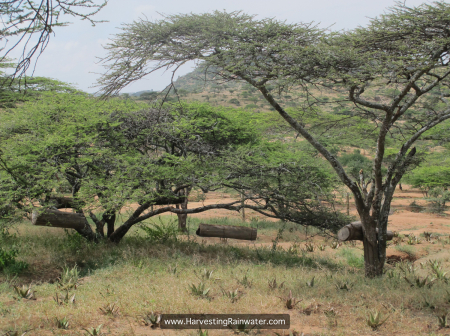

Many of the common pasturelands/wildlands that I saw on the Laikipia Plateau were deforested and degraded by extreme erosion. As I mentioned earlier, this was due in part to growing numbers of grazing livestock and less-active management of that livestock since kids who used to shepherd the animals now go to school instead. This results in the livestock moving less and therefore overgrazing areas, whereas in the past, shepherds and predators kept the livestock moving, lessening the impact on any one area.

But in the adjoining wildlife preserves I drove through, the land was healthy. These preserves were also grazed by the Maasai’s livestock, but the grazing was much better managed. Rotational grazing and holistic management were some of the management methods used.

My point is, the problem was not the grazing itself, but how it was—or was not—being managed. The “how” is essential in our assessment of problems and potential solutions.

So often, all we need is already around us, and within us, we just need to see it, then have the will to act and consciously evolve. The people and communities I have highlighted above are doing a great job striving to do just that.

Thanks to Joseph Lentunyoi of Laikipia Permaculture Centre (which is a whole other wonderful oasis), and to Maite Guardiola for making my Kenya visit and learning possible. And thanks to the TOPS Program and MercyCorps for bringing me to the continent to teach and learn still more.

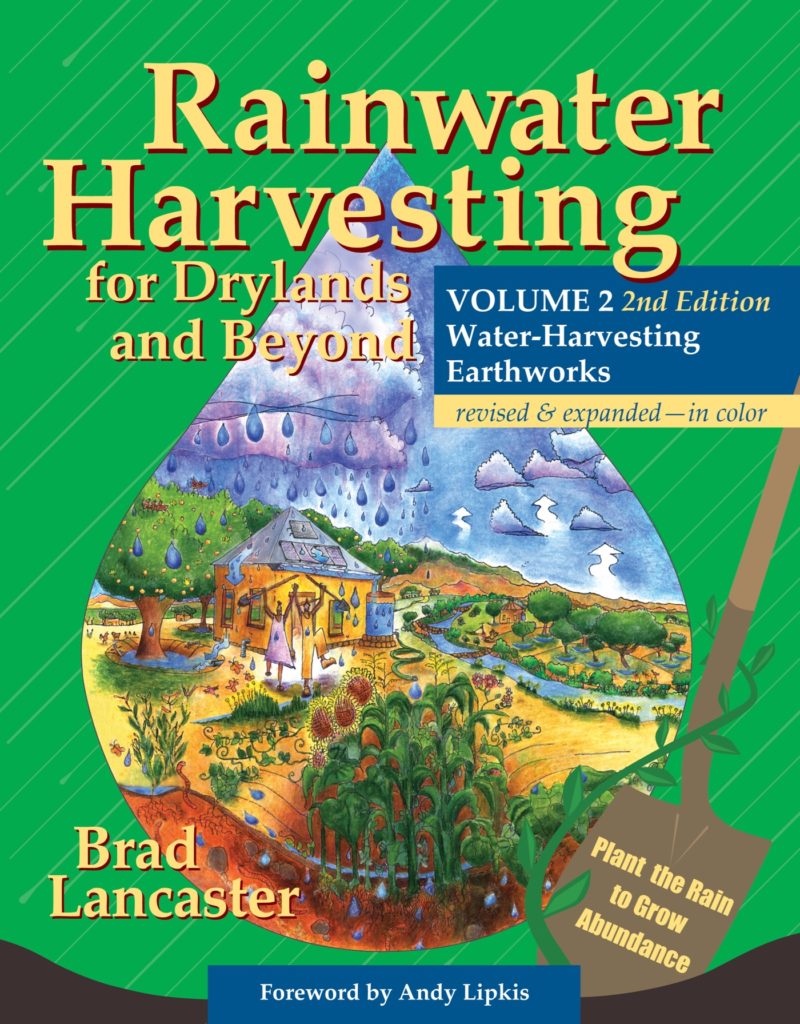

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1