Evolutions on Mr. Phiri’s Water-Harvesting Plantation, 1995–2016

by Brad Lancaster © 2016

www.HarvestingRainwater.com

Earlier this year I had the opportunity to return to Zimbabwe and to the farm of some of my prime water-harvesting mentors, Mr. Zephaniah Phiri Maseko and his family. While in the region, I also visited the farms of many other innovative farmers who are enhancing their soils’ hydrology and fertility by cooperating with natural systems. In this blog entry, and some to follow, I will share some of the inspiring things I saw.

I was in country with fellow colleagues Warren Brush and Thomas Cole to share and learn with model farmers affiliated with the Muonde Trust, and to work with a USAID-funded program that facilitates the training of technical field staff working with smallholder farmers (small-scale family farms).

My trip began with revisiting the farm of Mr. Phiri and family. In 1995 Mr. Phiri set me on my water-harvesting path by way of his productive example of numerous innovations and applications of very effective and accessible systems that plant the rain throughout his land with simple water- and fertility-harvesting earthworks. From that experience, I realized we all already have what we need to enhance our lives and those of others wherever we live—we just need to learn to see what is naturally and freely at hand, and then to live and work cooperatively with those resources and opportunities, rather than against them. For example, we need to plant/infiltrate/invest rainfall within our soils, vegetation, and watersheds rather than wastefully drain it away, and to do so in a way that enhances the health of all life, rather than benefiting some at the expense of others.

Since Mr Phiri’s learning kept pace with him over the decades, through this blog entry I will share a number of photos comparing what I saw on his farm in 1995, again on a visit in 2014, and on my latest visit this year (2016). Things kept getting better and better—not because of more and more investments of money into the farm, but due to better and better cooperation with the natural systems at play.

This blog entry is meant as a supplement to chapter one of my award-winning book, Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 2nd Edition, where you will find Mr. Phiri’s story, his water-harvesting evolution, and universal water-harvesting principles that were derived in part from his innovations and learning. I recommend you read that story first, then read on here to see how things have evolved.

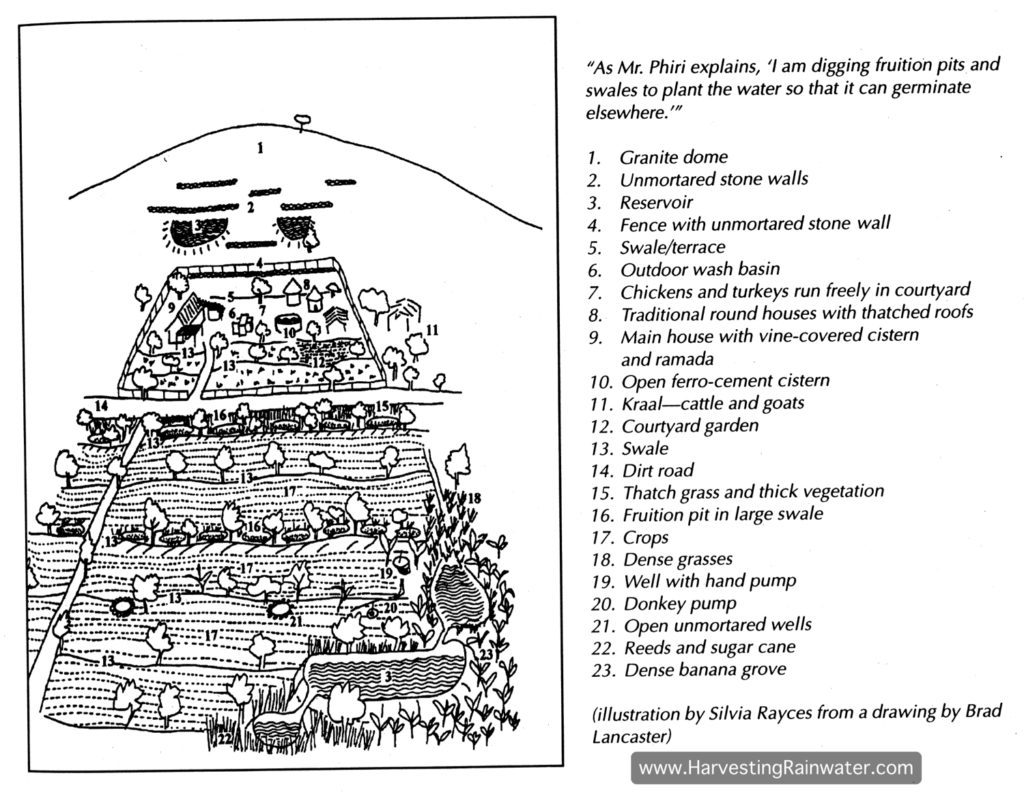

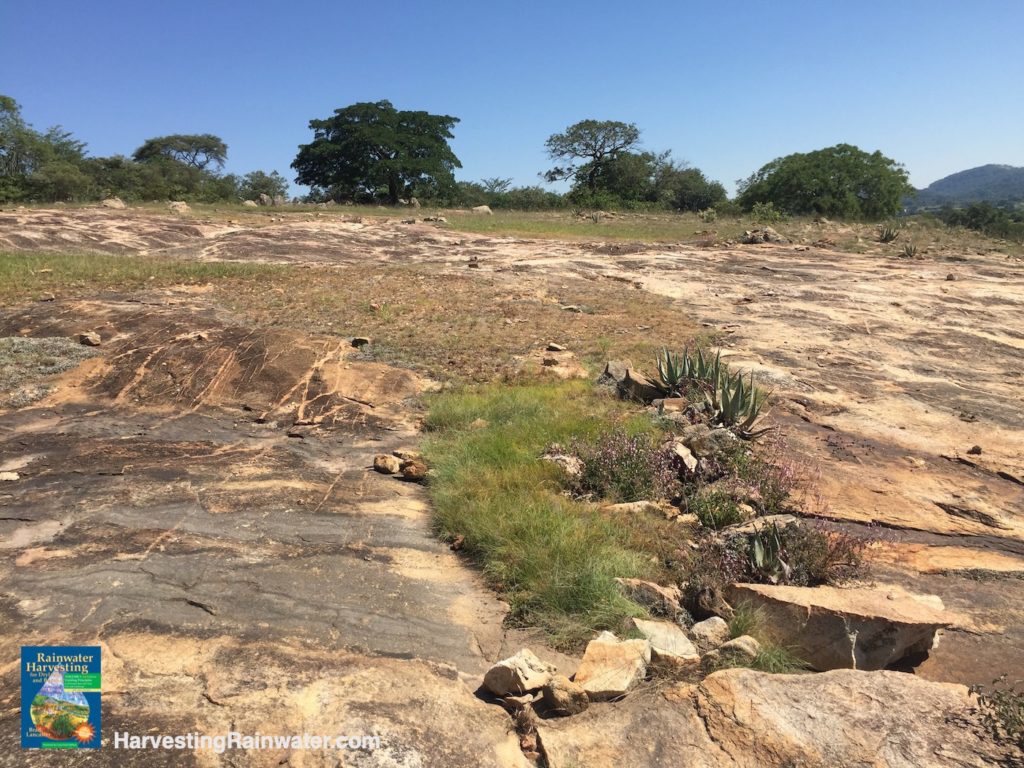

On the eroded hill slope above his farm, Mr. Phiri noticed that rocks placed across the slope could slow down stormwater-runoff flow, allowing sediment to drop out of the flow and accumulate behind the rock. Thus soil was captured, rather than lost. Moisture lingered. Seeds germinated. Plants grew, and a living sponge started to form on what was previously a bare bedrock drain (see images below).

Rocks, laid perpendicular to slope as a water and sediment trap. This is very near the top of the watershed that had been eroded down to bare bedrock

Compare to next photo, taken 21 years later.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Compare to previous photo taken 21 years earlier, as both were taken from same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

See Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition, for two variations of this strategy: sheet-flow spreaders and one-rock dams.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 2014 wet season.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 2014 wet season.

At the keypoint of the land, where the steeper, erosional section of the slope becomes more gradual, soil starts to settle out of the runoff flow and creates deposits.

Above and below the keypoint, Mr. Phiri created low, unmortared stone walls to slow and spread the flow of stormwater runoff (thus gathering sediment behind the walls – see images below). Just below the keypoint he created a small ephemeral reservoir dug down to bedrock. He digs out the sediment that accumulates behind it after a storm, then uses that sediment elsewhere for building projects, berm reinforcement, etc.

Dry-stacked stone walls and ephemeral reservoir near the base of the top of the watershed that had eroded to bare bedrock.

Compare to next photo, taken 21 years later.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Compare to previous photo taken 21 years earlier, as both were taken from close to the same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Many of the livestock pens are placed just below the keypoint of the slope, where the steepness becomes more gradual, and soil begins to settle out of runoff flow, rather than running off with it (see image below). As these pens are located above the farm’s fields and orchards, it is easier to work with gravity when moving the manure and its fertility downslope.

Placed here, it is easy to work with gravity to move the manure and its fertility downslope as needed.

Photo: Brad Lancaster, 2016 wet season.

Mr. Phiri calls his larger ephemeral reservoir his “immigration center” for the rain. See Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition, for the inspiring reason why he named it so. If this reservoir fills three times in a year, he knows he has enough water stored throughout his soil to last him through a two-year drought—due to hundreds of small structures and plantings throughout his land which all slow, spread, and infiltrate rainfall and runoff into his soil and the root zone of his plants.

Compare to next photo taken 21 years later, as both were taken from same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Compare to previous photo taken 21 years earlier, as both were taken from same vantage point.

Mr. Phiri’s son, Qaphelani (left), and Mr. Phiri’s grandson, Amon (right).

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Compare to next photo taken 21 years later, as both were taken from same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Compare to next photo taken 21 years prior, as both were taken from same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Greywater from the concrete washing station drains via a pipe into a shallow, unlined subsurface pit to freely infiltrate the soil and irrigate roots of surrounding perennial plants.

Compare to next photo taken 21 years later, as both were taken from about the same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Dishes are drying on the concrete washing station after having been washed. The wood structure behind is where grass and other livestock fodder are stored, out of reach of livestock.

Compare to previous photo taken 21 years earlier, as both were taken from same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

See Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volumes 1 and 2, for many other inexpensive, effective greywater-harvesting systems.

Mr. Phiri made “fruition pits” within a government-built drainage swale beside a dirt road (see below) to turn the water-draining swale into a water-harvesting structure. When a pit fills with water, the excess overflows to the next pit in the swale. Once rains stop and water stops flowing, all pits are filled with water that infiltrates into the on-site soils.

Compare to next photo taken 19 years later, as both were taken from about the same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Compare to previous photo taken 19 years earlier, as both were taken from same vantage point.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

They are called “fruition pits” because as Mr. Phiri explained, he grows many food-, medicine-, and fiber-bearing plants on the water harvested within the pits—thus they are very fruitful structures. He then picked some fruit from one of the bushes and gave it to me to eat.

Eat your rainwater.

Due to all the water-harvesting earthworks and plantings on the farm, the well (borehole) overflows in the wet season (see image below). The surrounding trees use that water, accessed via their roots, with excess directed via plastic pipe to different contour and diversion swales to further spread and cycle/recycle the water across the farm (see images below).

Photo: Brad Lancaster

In the video clip at this link, Qaphelani Phiri explains how excess water overflowing from the top of the hand-dug well is directed via plastic pipe to different swales below, 2016 wet season.

Notice how many perennial food-bearing plants are planted along these swales. Their roots are where gravity freely distributes the water. Excess water from these swales is directed into other swales (see next two images), hand dug wells below (next image gallery), and/or reservoirs below.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

If needed, water could also be pulled with a bucket from the nearest swale and applied to new plantings.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

There are a number of hand-dug wells on the Phiri farm into and from which water is both deposited and withdrawn. In the wet season, excess water from Mr. Phiri’s contour swales is directed into the wells below via plastic pipe, as well as in the form of moisture migrating more slowly within the soil itself (see images below).

Excess water from Mr. Phiri’s swales is directed into the well via the plastic pipe, and by moisture migrating more slowly within the soil from the swale upslope.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Mr. Phiri plants, infiltrates, and invests much more rainfall into his soils than he extracts or withdraws from his hand-dug wells. He gives back more than he takes. As a result, the water level in his wells keeps rising. He is continually increasing the amount of water he has stored in the savings account of his soils and on-site groundwater table. Thus he does not run out of water.

Mr. Phiri’s adjoining neighbors and those downstream have also benefitted from the Phiris’ work, as their well levels have also risen due to how much water the Phiris are inputting to the watershed.

However, others farther off in the area who do not harvest their rainwater find that their well levels continually drop and they must continually dig their wells deeper—and yet they still go dry since they extract or withdraw more water than they invest or deposit within the system.

Near the bottom of the Phiri farm are three ephemeral ponds stocked with fish to provide food, mosquito control, and fertilizer (see images below). If one pond goes dry, the fish are moved to the other ponds. If all ponds go dry, there is a community fish fry.

Fish are raised here and control mosquitoes while producing food and fertilizer.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

The tree in the previous photo blew over in a big storm a couple of years before this photo was taken, but much more vegetative life has grown to help shade and cool the water in the reservoir while also protecting it from the wind—all of which reduces water loss to evaporation.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

I found it amazing that some non-water-harvesting farmers in the area had dry wells, while the water-harvesting Phiris had full ponds with fish—another benefit of the abundant harvest of rain throughout the farm’s earthworks and soil.

In 1995 Mr. Phiri was using a pump typically powered by a donkey to pull water from the reservoir below to irrigate his field in dry times (see image below). Now, water harvested within the swales above, along with that in the reservoirs, passively infiltrates into the root zone of the plants. Thus the donkey pump is no longer needed or used.

Photo taken in 1995 dry season and drought.

The pump is no longer used now that water harvested within the swales above, along with that in the reservoirs, passively infiltrates into the root zone of the plants.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

Something I found very troubling in Zimbabwe, and which I find to be the case almost everywhere including in the United States, is how destructive agriculture can be in the way it is so often practiced. The land for the field in the photo below (and decades ago on the Phiri farm) was cleared of productive native forests to grow annual crops. With perennial vegetative cover gone, the natural water-harvesting sponge of the forest was replaced with a drain of seasonally bare, disturbed earth. Erosion increased greatly and huge amounts of soil and fertility were—and continue to be—lost.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

The Phiris have done a tremendous amount of work to try to undo that destruction. Water-harvesting earthworks now provide much of the sponge-services the forest vegetation and its mulch once provided. The planting of food-bearing perennial crops along those earthworks is also establishing a new forest of different species that continues to grow. Since 1999, the diversity of perennial plants on the farm has increased by 25%. Though what I find particularly insane is that many of these healing practices were illegal not that long ago. When Zimbabwe was still called Rhodesia, farmers were fined for having trees in their fields.

Thankfully the Phiris and many other rebellious, innovative farmers have proved the benefits of less harmful, and even healing strategies; thus these positive examples are helping change laws and practices for the better.

I plan to feature a number of these other farmers in upcoming blog entries. One of them is Lucy Dube (see photo below). Lucy was one of about a dozen women farmers who apprenticed with the Phiris in 2013 and 2014, and she has gone on to generate amazing water-harvesting examples, innovations, and teachings in her own right.

Lucy was reporting back to Mr. Phiri and others about what she had done after her apprenticeship with Mr. Phiri. Unfortunately I did not capture it in this photo, but she, like Mr. Phiri, is such a gifted storyteller and teacher that she had us all in stitches of laughter, wide-eyed with aha moments, and in tears. But in those moments I was too transfixed to take a photo.

Photo: Brad Lancaster

I donated money to the Muonde Trust to help make this apprenticeship happen, and recently did so again for a new round of such collaboration.

You could do the same, at Muonde.org.

And I strongly recommend that you do, as your contribution will go very far with this tremendous grassroots organization.

Mr. Phiri passed away in September 2015. His wife Constance, son Qaphelani, and grandson Amon are carrying forth the legacy as they continue to plant water and fertility on their land—and that of others—through their teaching, sharing, and inspiration.

Such teaching-by-example and sharing inspire many other Phiri-ites, who inspire still more. I consider myself one, as I do the many thousands who have read my books and are now practicing the planting of rain and the ecological growing of food in their lives.

The Phiri Award annually highlights such leading practitioners and innovators in Zimbabwe. (I plan to blog soon on some of the winners I visited (here’s one).

Similarly, in Rajasthan, India, a village of water harvesters, Laporiya, has inspired hundreds of other villages to likewise create sustainable oases in the desert by planting, not draining, the rain. They too have created an annual award, the Diamond of the Land award, to recognize leaders and innovators in their area. See their story in the introduction of my second book Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2: Water-Harvesting Earthworks.

Who could be the spark in your neighborhood or watershed?

It could be you!

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1

This is the book to start with for the integrated harvest of multiple free, on-site waters.

Includes the story of Mr. Phiri and his family’s transformation of their property into a water-harvesting oasis, and how they and others have realized the eight water-harvesting principles.

Volume 2

This book gives you step-by-step instructions on how to create many different types of water-harvesting earthworks for different conditions and contexts, and grow well-suited vegetation that will thrive without you after establishment.

Includes many inspirational water-harvesting stories from around the world, including the once-dying village of Laporiya in Rajasthan, India that rejuvinated itself and its watershed with water harvesting, and then when on to inspire and teach many other villages to do likewise.