Revised Multi-Use Rain-Garden Lists for Tucson, Arizona (and a template for anywhere else)

by Brad Lancaster © 2014

www.HarvestingRainwater.com

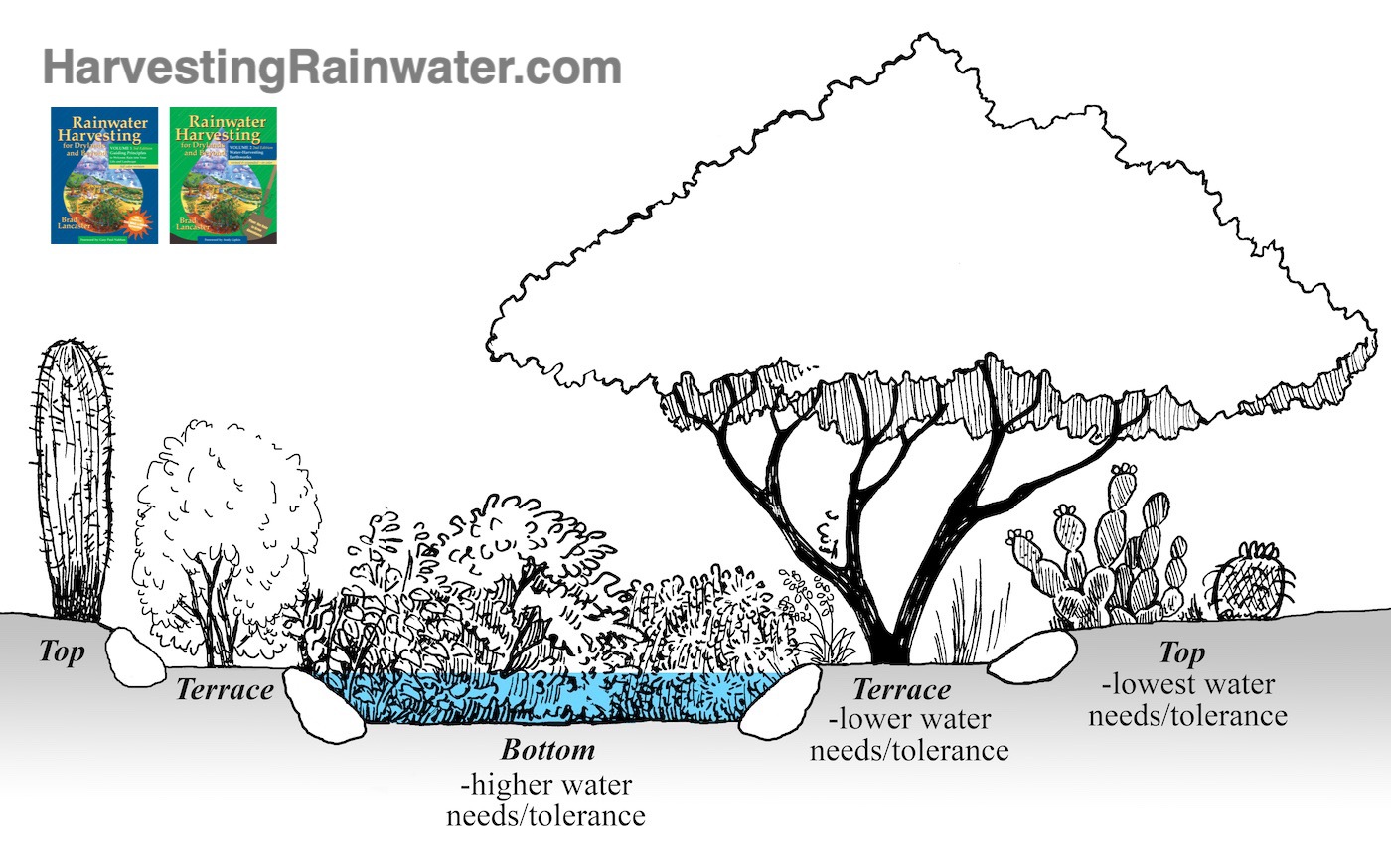

In the latest reprinting of “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, 3rd Edition,” and on my website I have revised appendix 4 by adding a Rain-Garden Zone column to the plant lists. The column indicates the ideal planting zone/location(s) for each plant within or beside a rain garden based on the plant’s water needs and tolerance—best placements listed first. There are three rain-garden zones:

Bottom – typically bottom of a basin or swale.

Prone to temporary pooling of water and cold air (cool night air pools in low spots).

Terrace – typically atop a terrace or pedestal within, or on bank of, a basin or swale.

Shallower and less-frequent temporary pooling than in bottom zone.

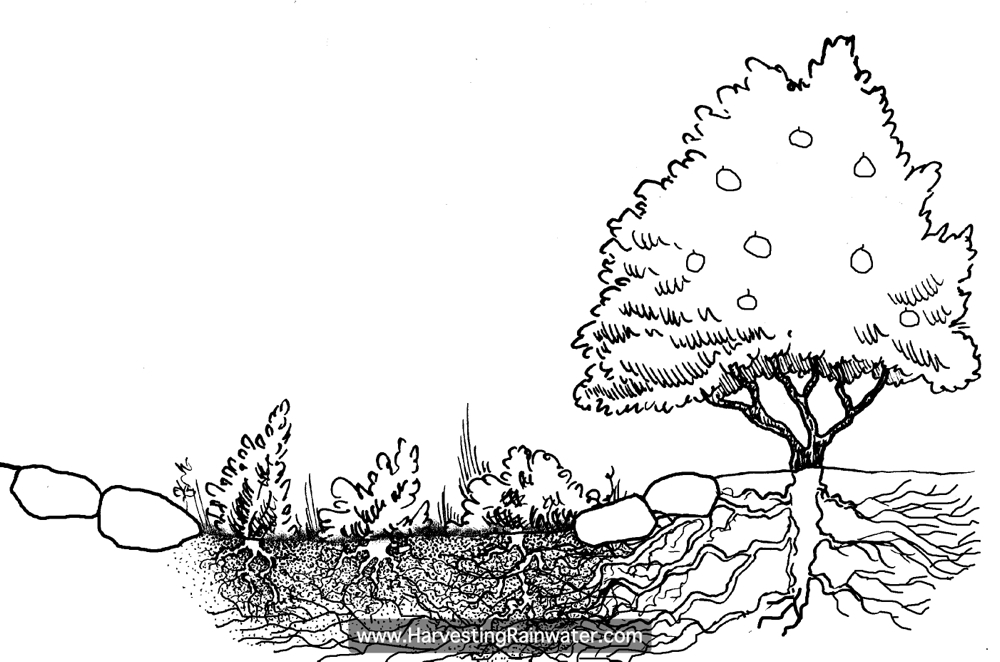

Top – area beside, not in, a basin or on its banks, where plant’s root crown stays high and dry, but plant’s roots can access water harvested in basin; top of berm.

Driest and warmest of the three zones (avoids cool air pooling).

Note that the Rain-Garden Zone can also be used as a Greywater-Garden Zone when greywater is discharged into a water-harvesting earthwork or rain garden.

I have purposely tried to keep this Rain-Garden Zone classification simple, so when working with a team planting a rain garden, each plant can be marked on its planting pot (before planting) with its ideal Zone. All plants (in their pots) can then be placed in their ideal rain-garden zones within or beside the water-harvesting earthwork. Once you have everything where you want it, the planting can begin.

Plant nurseries can enhance their offerings by adding plants’ ideal Rain-Garden Zone to their plant-identification signs. In addition, they can group Rain Garden plants by their ideal Rain-Garden Zone to make things more convenient for their customers. Customers who need a plant suited for the bottom of a basin can simply go to the bottom Rain-Garden Zone plant section. Customers will be especially happy if the nursery has demonstration rain gardens with established/mature specimens. Seeing is believing—and understanding.

But what if you don’t live near Tucson, Arizona? Use the structure of the Tucson plant guides to create your own lists (listing plant water needs, rain-garden zone, mature size, cold tolerance, human uses, wildlife and domestic animals that like to eat from the plant, etc).

I created these multi-use plant lists partly as a reaction to rain-garden plant lists that I found to be frustratingly limited in their information. All too often they just gave the rain-garden zone and flowering times of the plant. There was no information guiding plant choices that could generate resources beyond ornamentation—such as food, medicine, pollinator corridors, summer shade, winter sun, livestock fodder, etc.

I also purposely separated native and exotic plants into different plant lists because I find the native plants to be the best suited for harsher microclimates which receive only direct rainfall and runoff. Plant the rain (in water-harvesting earthworks or rain gardens) before you plant the native and it should thrive rather than just survive.

The non-native exotic plants are better suited for more-protected, cared-for, and better-watered microclimates. I emphasize food-bearing plants in my exotic-plant lists, and I have a rule for such exotics: Before I plant the exotic fruit tree I always first plant greywater (with a gravity-fed greywater-harvesting system) where that fruit tree will go. That way it will have the water it needs without being dependent on a conventional irrigation system that wastefully uses virgin drinking water rather than free on-site waters such as rainwater, stormwater, and greywater.

See my books for how to best plant your free on-site waters. And see the Vegetation chapter of Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 2, for how to get and use such local plant information. Though it basically boils down to this: Go take a hike!

Walk in relatively undisturbed areas of your local ecosystem and see what plants grow in the low spots periodically inundated with water and sediment—those are your bottom-zone species.

What plants tend to grow on the banks, rather than in the bottoms, of depressions? Those are your terrace-zone species.

And which plants like to be able to access the water harvested in a basin with their roots, while keeping their root crown (at the base of the plant’s trunk) high and dry to avoid crown rot? These are typically fruit trees and they are your top-zone plants.

But note that these delineations are context-specific. For example, a plant in the list noted as being best suited for a terrace Rain-Garden Zone when planted within a water-harvesting earthwork (where it is assumed the rain garden will receive direct rainfall AND additional water from incoming runoff, such as from a roof or other surface), may actually be better suited to be planted in the bottom zone of a rain garden if that rain garden receives only direct rainfall—no additional runoff. In short—the plant lists are guides, not absolutes. Question them based on your own experience, and modify them if you find they could be improved. That way things keep evolving—just like life.

In that same spirit, help us grow and enhance these resources. If you create such rain-garden lists for your area (based on this or a similar multi-use template), and would like them posted (and credited to you as the creator of those lists) in the Multi-Use Plant Lists Resource section of my website, send them to admin@HarvestingRainwater.com, and let’s see things really grow!

Special thanks to James DeRoussel at Watershed Management Group for helping me create and refine the Rain-Garden Zone terms.

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1