Cisterns of Old Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

or If You Pray for Rain – Harvest It

By Brad Lancaster

www.HarvestingRainwater.com

Number 2 in a series of Drops in a Bucket blog entries on Brad Lancaster’s and David Eisenberg’s U.S. State Department-sponsored adventures and gleanings in the Middle East

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, April 2009

Most of the water people now drink in Saudi Arabia is desalinated seawater. And there are great costs, among them air pollution from the power plants which burn oil to run the desalination plants. We read articles daily on the many people falling ill from the pollution.

The new Saudi Arabia is very dependent on this oil, not only for water, but for the mechanical heating and cooling of the new modern buildings of imported concrete, steel, and glass.

The new Saudi Arabia is very dependent on this oil, not only for water, but for the mechanical heating and cooling of the new modern buildings of imported concrete, steel, and glass.

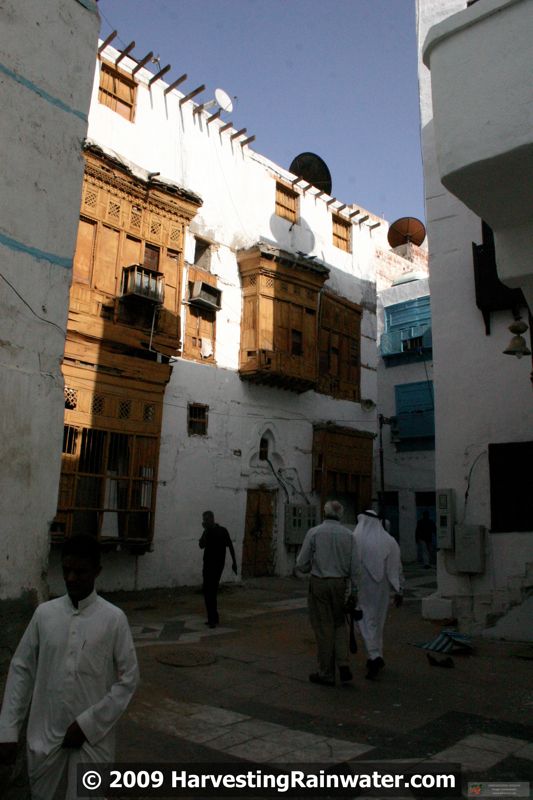

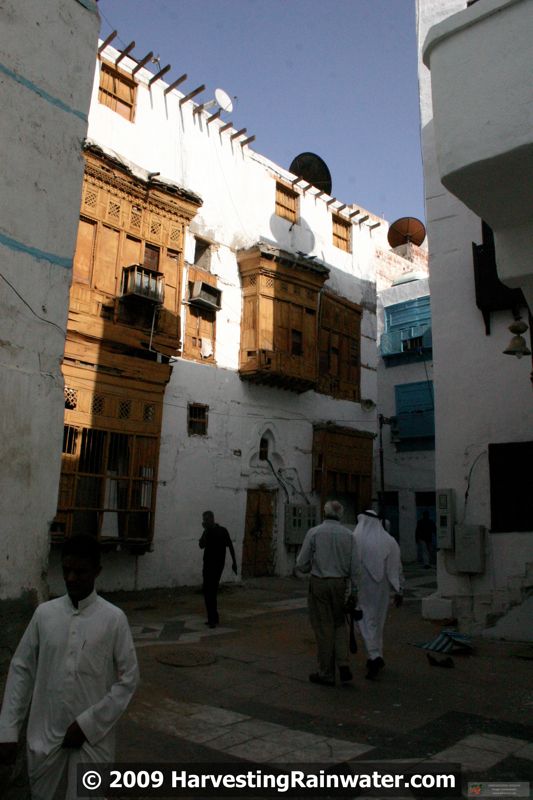

But the traditional dynamic Saudi culture was borne from surviving and thriving in this hot, dry climate — without oil, imported building materials, or appliances. We wanted to see the old practices of harvesting water, building with local materials, and passive cooling and heating. So, we headed for old Jeddah.

Old Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, is a gem, and as our guide Sami promised, it is replete with a rich tradition of harvesting rainwater, life, and vernacular architecture. Sami Nawwar was our lively host. He is caretaker of the grand Nasseif House/Al Balad at the core of old Jeddah. Sami is hugely excited about old Jeddah and has been fighting to save it for over 40 years. (Throughout our travels we saw the rapid demolition of the old, earthen or coral, passively cooled, pre-oil sections of cities and towns to make way for imported-resource-dependent modern buildings.)

Into the Nasseif House we went. The ceilings are very tall to gain the benefits of passive cooling. Ample shaded windows catch cooling sea breezes. And the walls are made of coral brick interlaced with wooden bond beams, of sorts, every five courses or so to make the building safer in earthquakes. The staircase was built very wide with short steps so horses could easily climb to the top.

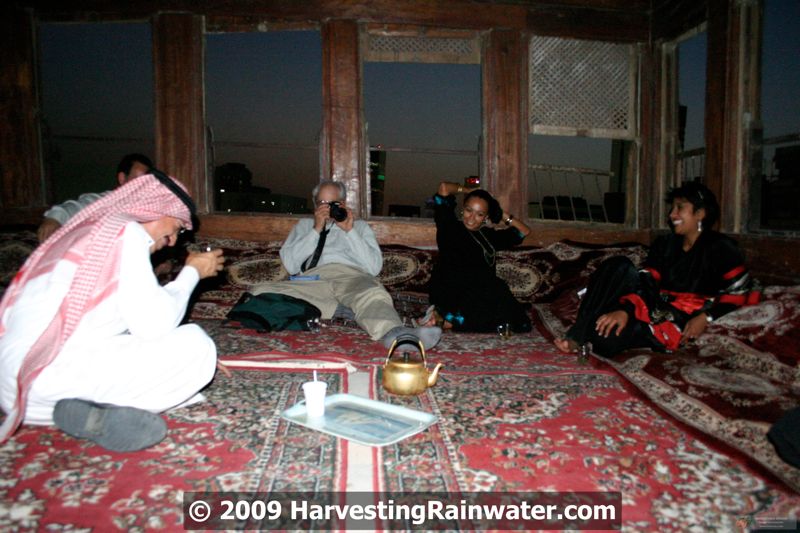

Then evening prayer began and Sami shouted, “Quick, to the top! You must hear the prayers from the roof!” From every direction came the call to prayer, rising and falling like the chaotic roof lines around us. Amazing. As the sun set and darkness fell over the city we had tea on the roof, the cooling breeze refreshing us.

In the heyday of Nasseif House/Al Balad, children would sweep off the roof before the rains, and the rainfall would be directed to downspouts taking the water to the huge basement cistern. All non-human waste was composted or fed to livestock. Human waste went into a septic tank that was cleared once a year, then washed with salt. (I did not find out where the human waste went after being cleared from the septic tank.) [Entry continues below.]

BREAK]

“We’re late, we’ve got to go!” our U.S. State Department chaperones informed us. But Sami had promised he’d take me inside a neighboring cistern. I shot him a look. “Follow me,” he said, and we ran past the group. We rushed out of the building, down the street, and along the old mosque.

Turning sharply we entered a modern women’s clothing shop, and sped to the back. Sami stopped in front of a dress hanging on a wall and said, “We are here.”

He then pushed the dress aside, revealing a hidden door. We stepped down into a massive cistern with vaulted ceilings. It was the cistern for the mosque. I was having so much fun. We had entered a hidden world, feeling something like the half floor in the movie Being John Malkovich. It was also further confirmation that every culture with a dry season has a tradition of water harvesting, and Jeddah was no exception. With just over 2 inches (50 mm) of rain a year it was not only possible, but absolutely necessary. [Entry continues below.]

These cisterns are seldom used today, what with the temporary abundance of plumbed and pumped distilled seawater, but I feel they are a major part of the solution for the past, today, and the future. These cisterns were the water source of the past. And they could be the, or at least a considerable, water source of today and tomorrow. They work on gravity, not pumps. They do not require pipes throughout the city, only pipes from every roof to a tank below. Beneficial redundancy and resiliency. They also reduce flooding.

Jeddah gets little rain, but most of it comes all at once in big downpours. After our visit floods did major damage in Jeddah. Sprawling construction of new buildings and roads is occurring all over, paving ever more of the watershed. Unfortunately the runoff from this new infrastructure (and the old) is now directed to streets rather than tanks. Thus these floods are more human-created than weather-created.

There is a rich history of praying for rain in this dry country, but the management of that rain has been largely forgotten with the temporarily available “cheap” oil and desalinated water. Much of the answer to those prayers lurks under floors and behind dresses, waiting to be remembered.

See Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volume 1, for more on this topic. And click here for information about the Arabic edition of Volume 1, released in Spring 2011.

See the new, full-color, revised editions of Brad’s award-winning books

– available a deep discount, direct from Brad:

Volume 1